According to the WHO, over 5% of the world population (430 million people) require rehabilitation to address their disabling hearing loss. In this same webpage, they describe hearing loss as being unable to hear the hearing thresholds of 20 dB or better in both ears. Two terms are used to categorize hearing impairment: Hard of Hearing and d/Deaf. “Hard of hearing” refers to people with mild to severe hearing loss whereas “d/Deaf” refers to people with profound hearing loss, little or no hearing. Hearing loss can be congenital, a symptom or consequence of a condition, progressive, age-related, or simply temporary, but its permanence or cause does not remove its importance from accessibility considerations.

Most frustratingly, despite many features being available, they are often done wrong, sloppily, or, in some cases, make functionality worse. For example, automatic captioning is widely used on YouTube, but rarely conveys correct dialogue or information. There have been several cases of unqualified interpreters signing gibberish at press conferences and other professional settings as well, making accessibility seem more of an afterthought than a real concern. One interviewee stressed that sometimes it takes large consequences for a company to even add the accessibility feature for the deaf. Take Netflix, for example, who was sued by the National Association of the Deaf for not providing captions in 2011. Now, they provide the guidelines for subtitles (how the tables have turned!).

Based on my interviews with industry professionals and those with auditory impairments, these are the accessibility best practices to assist with these impairments. At the bottom of the page, you will also find the checklist for auditory accessibility.

Captions

While it may seem obvious, captions are a big topic for auditory accessibility and also seem to have the most problems. First it’s important to know the difference between subtitles, closed captions, and SDH. Subtitles refer to spoken dialogue ONLY. Closed captioning refers to spoken dialogue and audio cues/information that is not visually conveyed to the user. SDH (Subtitles for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing) combine the two. SDH requires the exact script to be used and the dialogue to be exactly transcribed; however, rules can also be changed per jurisdiction.

The important thing with captions is to make sure that the captions are reviewed by a LIVE PERSON. At the beginning of this article, you’ll see that there is an example of automatic captioning that is so completely wrong from the source audio. This is the result of adding the feature without post-editing. Automatic captioning is seen as a way to cut corners to add accessibility without transcribing EVERY video. On video streaming platforms like YouTube, content creators are responsible for captioning rather than the organization, so the feature tries to make everything accessible for everyone. Unfortunately, a computer cannot accurately transcribe a human voice with a 100% accuracy. So, whenever captions are made, it’s important to post-edit especially when you work with other languages.

With regards to how you should caption, there are a few things to keep in mind (these are adapted by the DCMP Captioning key and Netflix Subtitle Guidelines):

- Caption formatting

- No more than 2 lines of text

- Each line of text should not exceed 37 characters

- Captions should be centered on the top or bottom. (EXCEPTION: Japanese language where the subtitles can be placed vertically on the sides)

- Minimum duration: 5/6th of a second per subtitle event

- Maximum duration: 7 seconds

- Avoid overlapping on text

- Caption Styling

- Use sentence case capitalization instead of ALL CAPS.

- The line should be broken

- after punctuation marks

- before conjunctions

- before prepositions

- The line break should not separate

- a noun from an article

- a noun from an adjective

- a first name from a last name

- a verb from a subject pronoun

- a prepositional verb from its preposition

- a verb from an auxiliary, reflexive pronoun or negation

- Make sure the speaker is identified (ex. [Martha] I think we should go to the mall./[Jack] Yes, that sounds lovely.)

- Preserve the tone of the speaker as much as possible

- With sound cues that are not dialogue based, show the sound effects in brackets and in all lowercase (ex. [dog growls])

- You can choose to describe the sound or use an onomatopoeia

- this also should include music, off screen sounds, and sound cues that convey something vital to the viewer (such as a change in tone)

What the list didn’t include is how the subtitles should look. Ideally, you would allow the user to change the font, style, color, opacity, and size of the captions themselves, but if that option is not available. Make sure that the captions are visible, clear, and legible. That means no textures, backgrounds, or on-screen text should make the captions hard to read nor should the captions be too small or quick for the user to read them.

UI/UX Considerations

For apps, video games, and websites, there are still considerations you must take for people with auditory disabilities. For example, notifications need to have alternatives for sensory feedback. If a message is only convey to the user through sound, a deaf or hard-of-hearing user will not be notified. An easy way to circumvent the issue is to have the notification show auditorily and visually to the user, or having something like a vibration. The same goes for video games. Lots of video games use sound cues to alert the player that an ability is available, a move can be blocked, an enemy is around, etc. Giving different indicators for those focus cues makes it playable by everyone, not just those who can hear.

What may not seem so obvious is the need for different forms of contact. If your company only has the option of phone contact with no TTY, a whole group of users is alienated and unable to get support for your product. While it may cost more resources, consider having email, fax, text message, or even web chats available for your user. Something like a ticket center means the world to users who have no way of communicating verbally or being able to listen to someone on the phone. It should be noted that while not all people who are hearing impaired are completely deaf or unable to communicate verbally, having the options available gives them the power to choose how they contact your company.

Another important consideration is how you write your option titles. For most deaf people, according to an interviewee, they are not put in mainstream schools very often or do not have access to the same education. As a result, they may not have the same literacy levels as the average user. Make sure when you have setting/options that the titles and descriptions are written in simple plain English. This not only helps the deaf and hard-of-hearing but also for localization where translators have enough context to properly translate.

The last few considerations may seem obvious but they need to be done right. Firstly, is there a way for users to have auditory events transcribed to them? For things like podcasts and videos where captions are not always available, make sure or at least try to include a transcript to the user. This way they can still interact and engage with the product without jumping over hurdles. For video games, allow captions to not only do dialogue, but other on screen events as well. This can be as simple as a closed caption setting or as complex as adding different focus cues as mentioned in the first paragraph. Secondly, let users communicate with other users via text or have a speech-to-text/text-to-speech option so that they can still communicate with other players. We may not think this is completely necessary from the get go, but imagine trying to play a multiplayer game and having no way to communicate with your team. That makes it harder for everyone to enjoy it. Having this option gives players and users the ability to communicate freely in whatever means they prefer.

Here’s a great example of these considerations in practice from Naughty Dog’s The Last of Us Part II (taken from YouTube):

Sign Language

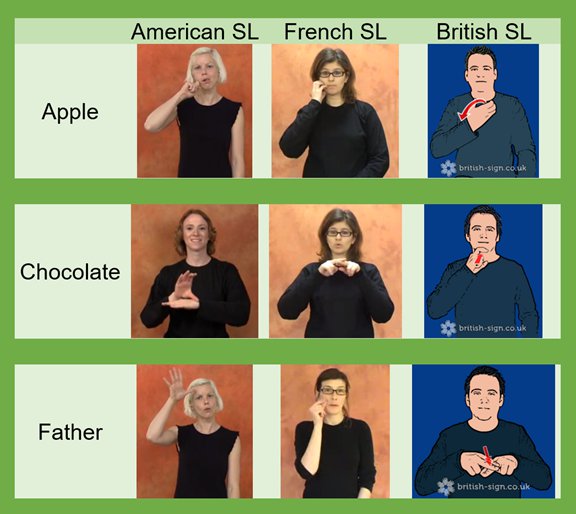

We can’t have an article on auditory accessibility without mentioning sign language. Sign language is a vital communication form for people with auditory communication. There also are different forms of sign language including: American Sign Language, British Sign Language, French Sign Language, and Japanese Sign Language. It should be noted that the different forms of sign language need to be treated as different languages NOT as the same dialect of the same language. While some sign languages may be derived from others, they are not mutually understood (see image below). So when you provide sign language, IF you provide sign language, make sure it is one that most of your audience can understand according to your locale.

Regardless of language, a visual signer, if used, needs to be seen on screen. If the viewer cannot see their hands and/or expressions well, they won’t understand what’s audibly going on on screen. The visual signer should also be movable and resizable where possible to allow the user to customize their experience. If this is not possible, aim for the visual signer to be in the user’s field of view and as legible as possible.

For online or in-person services or products, it’s important to have an interpreter or a TTY option available. Teletypewriter (or TTY) is a device that allows a text message to be audibly interpreted over telephone. For users that have a TTY, they can use the service themselves; for those who don’t, they can simply contact a TTY service that connects them through a message relay center. This provides an avenue of ways users can communicate with the company, support, or even storefronts.

Finally, if none of these options are available, there should be a non-verbal way to communicate. This can be as simple as providing a menu with pictures to point at or as advanced as having a self-service kiosk for customers. If neither of those options work, training workers or letting users type or write their request can remedy the situation. Again, make sure that users have multiple options and don’t make assumptions on what they need. Let them tell you what they need.